Written by Dr. Kalynda C. Smith

Edited by Manuel Galvan

Awareness of the Body Positivity Movement has ebbed and flowed over the last few decades. There has been a resurgence in discussions of body positivity due to a social media-fueled focus on physical appearances. The movement originated in the late 1960s, when Bill Fabrey founded the Body Positivity Movement to address and decrease fatphobia. The purpose of the movement was to recognize that those with bigger bodies, especially women, were discriminated against because of their appearance. The most recent incarnation of the movement has borrowed from other social justice traditions to embrace the beauty of people of all sizes, races/ethnicities, genders and atypical functions. While the body positivity movement tries to address the problem of stigma caused by physical appearance, obesity-related illnesses constitute a health crisis. In this article, we attempt to address what effects body positivity and body shaming have on these problems. What is the evidence for and against body positivity? Are there unintentional negative consequences to body positivity and, if so, what are some alternatives?

Body Positivity and its Discontents

Social media, particularly image-based media like Instagram, has changed the way that people communicate compared to more text-based social media. On Instagram more than other platforms, physical appearance is the central focus. Furthermore, because digital media has evolved to include advanced filters, individuals can now alter their faces and bodies, to digitally enhance their physical appearances. Instagram and similar apps have made people hyper-aware of their appearance. For those who have the idealized physical features, this hyper-awareness serves to protect their self-esteem, even providing a means for people to monetize their physical appearance. The “Instagram model” is an attractive person who is able to use their appearance to sell products on Instagram and similar apps. Their beauty is both real and unreal (due to the process of digital enhancement), but their prominence is a result of centering physical appearance on social media. Just as many opportunities arose from this change in social media that may have not been available otherwise, a darker side of the focus on physical appearance became more apparent. While “beautiful” people were lauded, those who did not fit the traditional definition of beauty were shamed. Trolling people who did not fit Eurocentric beauty standards became the norm on social media, regardless of a user’s type of post or message. The intolerance and vitriol from internet users led to a rebirth of the Body Positivity Movement.

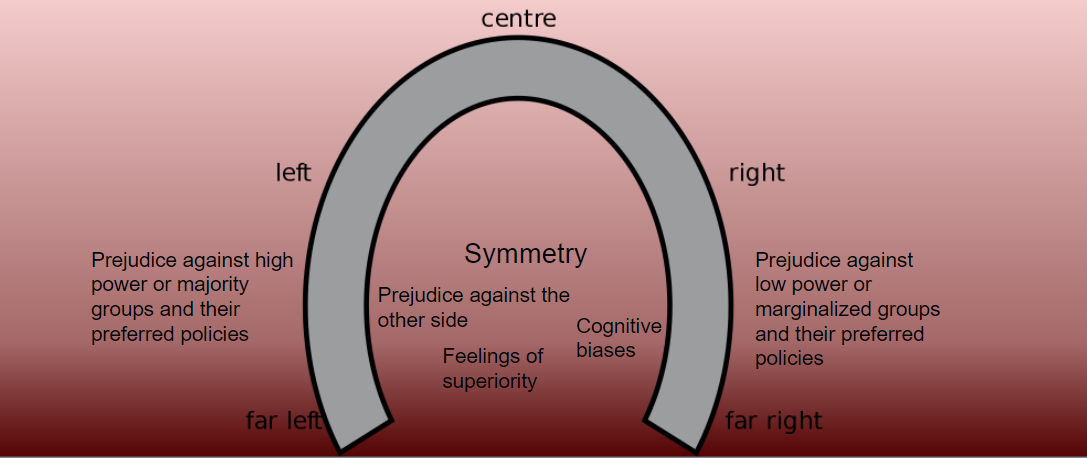

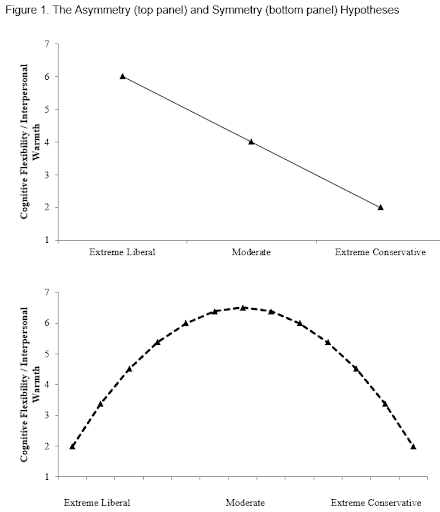

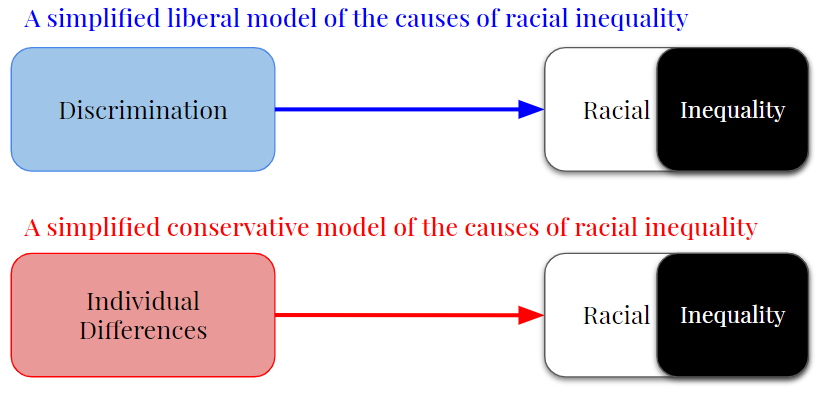

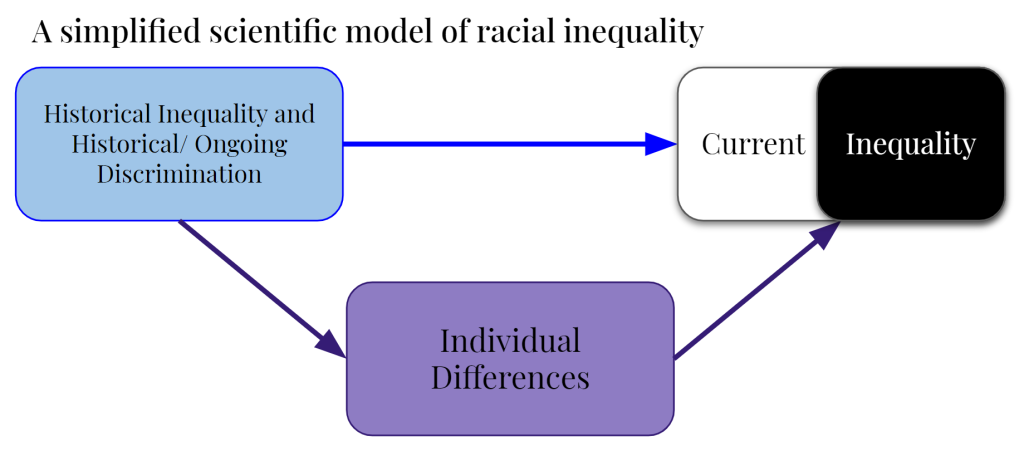

One of the critiques articulated by the Body Positivity Movement is that beauty is too often associated with thinness, Eurocentric features, White skin, and cis-gendered heterosexual femininity, while women with darker skin, plus-sized or divergent body types, and/or queer identities are unacceptable. Notably, body positivity very quickly became a political battleground; the proponents and opponents of body positivity emerged from the usual political camps of liberals and conservatives, respectively. Opponents tend to concentrate on size when discussing body positivity, arguing that people (typically women) with bigger bodies are unhealthy. They argue that calling “unhealthy bodies” beautiful is a disservice, because criticisms of weight can motivate overweigh people to improve their bodies and, ultimately, their health. One difficulty with this argument against body positivity lies in the assumption that bigger bodies are not healthy, but “bigger” is subjective. What is considered “too big” to be healthy has changed over time in the U.S. alone, and differs according to culture across the globe. Many well-known and oft-used Western measures of healthy body weight have had very little evidence of their accuracy especially across different body types and races or ethnicities. For, instance, the popular Body Mass Index (BMI) does not distinguish fat from muscle, and it has been found that African Americans are likely to have less fat mass than White Americans with the same BMI. This suggests that overweight and obesity ranges for African Americans should be higher than they are for White Americans. Another fallacy embedded in this argument is that public criticism and body shaming will result in motivation to exercise, eat healthy and ultimately lose weight. There is little empirical evidence to support this belief. The available scientific evidence suggests a nearly opposite conclusion: Fat shaming undermines a person’s healthy self-image and belief in their ability to manage their weight and the resulting weight stigma is more likely to push them away from exercise and towards unhealthy eating habits.

As previously mentioned, the issue goes beyond those who are simply for or against body positivity. While there is scientific and anecdotal evidence against the anti-body positivity arguments, there are also disagreements between people who support body positivity. Some have noted that the women, usually White cis-gendered wealthy celebrities, who have taken up the conversation have fairly typical or “normative” thin bodies. Body positivity has allowed these women to present their bodies in ways that they find more honest, exposing cellulite, stretch marks, and skin folds, which can be liberating for all women. However, body positivity began as a way to center the discussion on bodies that were not normatively thin, White, or cisgender as beautiful. Many argue that mainstreaming the movement has perpetuated the erasure of those who were meant to benefit from it. Yet, even as the movement fractures, it gains momentum, and still less of it focuses on the actual health of women’s bodies.

Health: What Matters Most

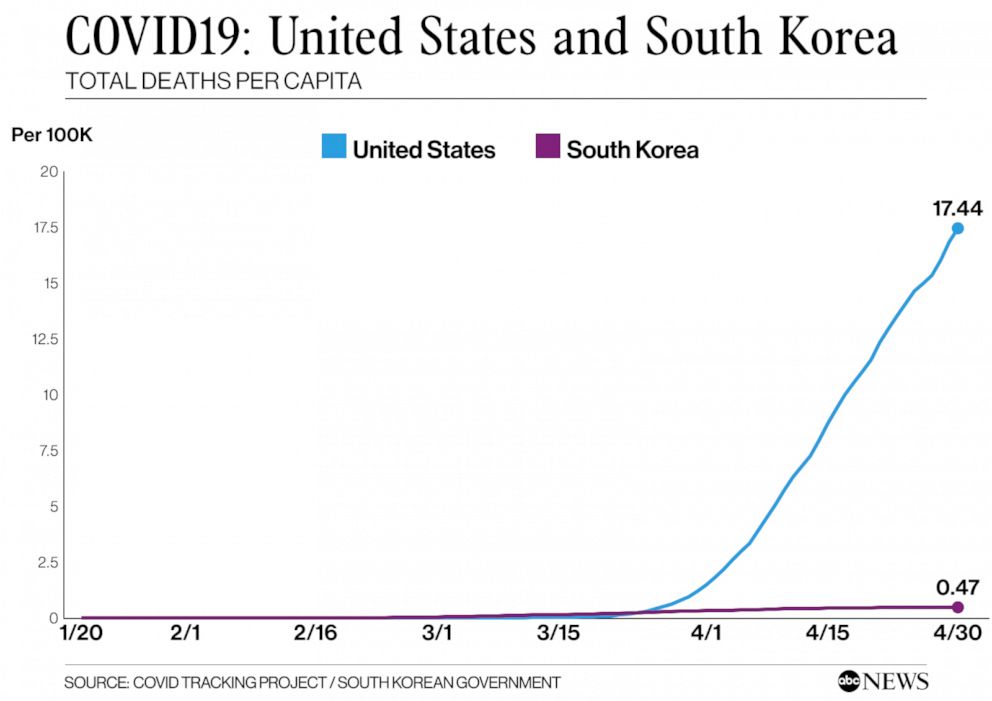

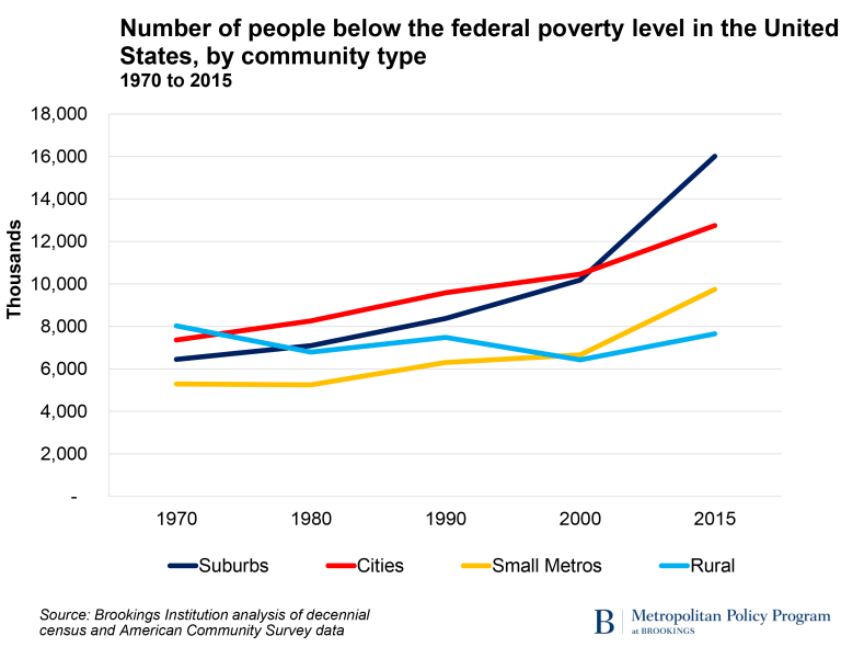

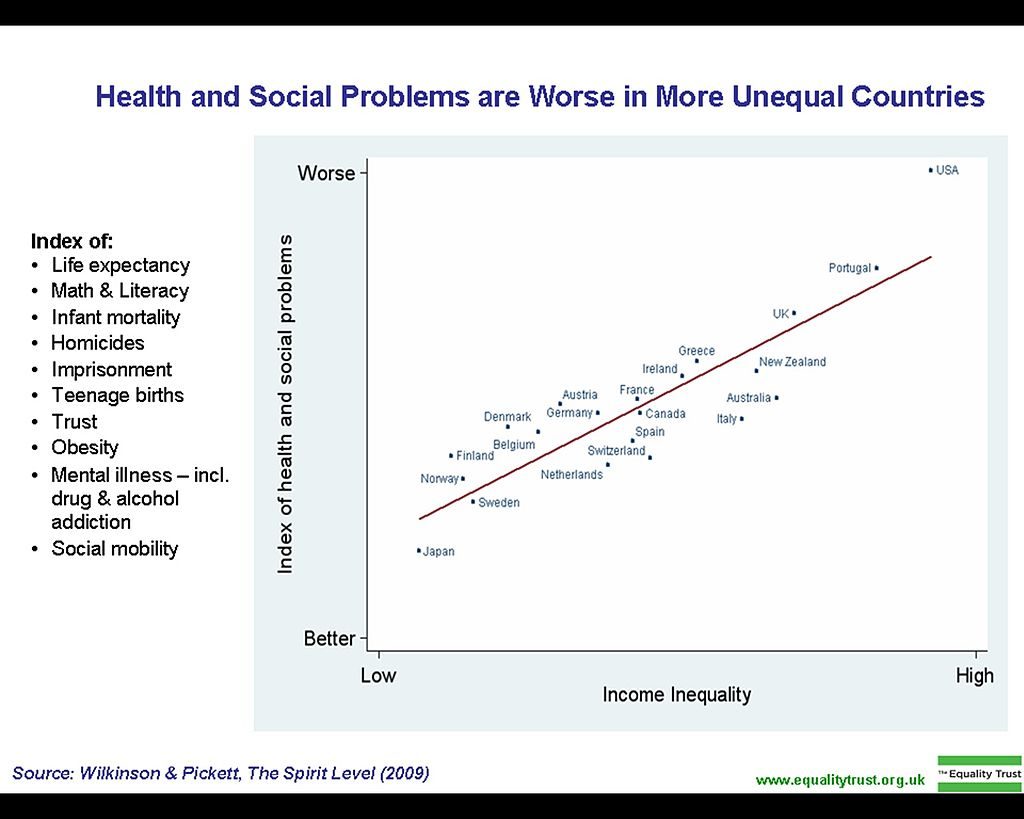

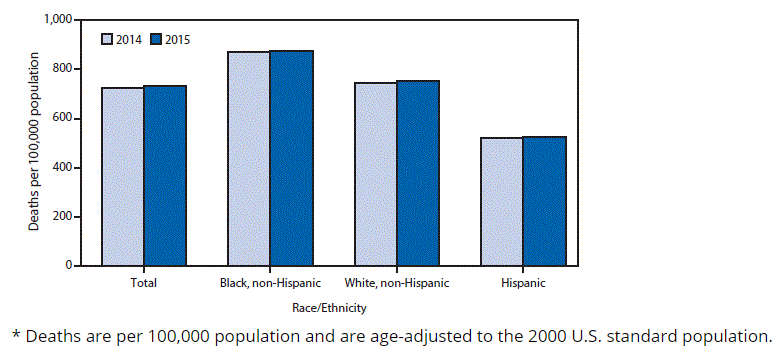

The prevalence of obesity has been on a steady rise in the U.S. and around the world in the last few decades. African American/Black women in the U.S. specifically have higher rates of obesity and over-weight status, creating a health crisis for these women. The risk factors associated with obesity are increases in the likelihood of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, some cancers, and more. These conditions can be fatal or result in severely lower quality of life for those living with any of these ailments. These diseases also incur significant healthcare costs, which are particularly burdensome for African American women who are economically disadvantaged in the U.S.. Size discrimination can also lead to poor mental health, such as an increase in depression and bulimia. Children especially are at risk of experiencing bullying based on their size. As already noted, size stigma and weight shaming just perpetuates negative habits like avoiding exercise and overeating (see research here, here, and here). While body positivity messages can serve as buffer to protect self-esteem and confidence, we need to consider the possible unintentional negative consequences. Without the correct framing and context, could messages in the name of body positivity lead to health habits and behaviors that increase obesity for at risk populations?

Currently, young women and girls receive many, if not most, messages about health, fitness, diet and beauty through social media. However, there is also inadequate policing of content, resulting in messages lacking appropriate context or messages that are unintentionally, or even maliciously, inaccurate. Messages about body image may be especially prone to being misconstrued on social media because they are heavily associated with consumerism. Diet books have been sold in the U.S. since the 1920s and are often a vehicle to spread pseudoscience and misinformation to vulnerable people (often women) who are desperate to find healthy ways to stay fit. Social media messages tagged as #thinspiration or #fitspiration are often the modern incarnation of the same predatory practices in those antiquated diet books. Thinspiration messages encourage viewers to participate in behaviors that will keep their bodies thin (lose fat), including encouraging and praising disordered eating. Fitspiration encourages viewers to focus on fitness (gain muscle) but are also likely to include messages that associate eating and overweight bodies with guilt or shame. These are some potential harms that result from fat shaming, but many are concerned that some body positivity messaging has swung to the other extreme, encouraging women to embrace obesity, despite the many harms that may come with it.

To ensure that body positivity messages don’t have unintentional negative consequences, body positivity messages should be paired with the evidence-based suggestion that women should monitor their physical health to improve or maintain their quality of life. Furthermore, those attempting to create body-positive images should be cognizant of characteristics of the bodies depicted. Many body positivity messages contain images of traditionally thin, White, able-bodied women or plus size women with a body type that is unrealistic for many – small waist, flat stomach, large breasts, hips, thighs and bottom – in sexualized poses. Some of these videos and pictures are posted in an effort to normalize bigger bodies, which is extremely important, especially for women of color who tend to have bigger bodies than White women; however, normalizing bodies that are large, but atypical in their proportions, does not necessarily advance self-love for the women who need those messages the most (i.e., women with proportions who do not fit the beauty stereotypes). Further, social media is more likely to be used by younger women whose health habits are likely to set the stage for their health for the rest of their lives (also see here). Messages focusing on looks instead of health are likely to be damaging for these young women, especially African American/Black women who are more likely to be plus size and develop conditions like diabetes with less resources to manage these conditions.

A Better Approach

The Health at Every Size approach eschews a preoccupation with weight and looks and instead focuses on health habits. While being overweight or obese is correlated with health risk factors, it is only one of many factors that are correlated with health and longevity (see here, here, here, and here). By expanding the conversation about health beyond just weight, the Health at Every Size movement shows much promise in addressing both health and positive body image. Health at Every Size messages highlight the benefits of healthy eating and maintaining good fitness habits. These messages are likely to increase healthy habits and prevent disordered eating compared to those espoused by thinspiration, fitspiration, or sexualized body positivity messages. These messages are also likely to be especially helpful to younger women as a preventative measure rather than as an intervention.

While the intent of the Body Positivity Movement started as a place of empowerment for plus size women, then moved on to celebrate all bodies despite race, gender, or ability, through social media, the current movement is so mainstream that it needs to be sure not to reinforce the very beauty ideals it intends to protest. The cyclical nature of beauty standards in the U.S. would suggest that perhaps body neutrality is ideal. Instead of reinforcing the importance of the beauty of bodies, which is subjectively defined and inevitably used as a tool of oppression by the dominant culture, it would likely benefit individuals and society to emphasize being appreciative and respectful of the bodies we have. Body neutrality allows us to normalize all bodies. The ideological debate regarding body positivity and the shame associated with thinspiration and fitspiration messages demonstrate the persistent belief that “what is beautiful is good,” which gets to the heart of the problem. We need to move beyond this focus on beauty. Our bodies allow us to live. They do not determine our worthiness as individuals or the quality of our character. When we can finally shed this divisive, inaccurate, and dangerous belief, we can then enhance the quality of every life, especially those already marginalized groups with so much more on their proverbial plates to deal with.